Apocalyptic Plagues and Anthropocene Forests: How Charles C. Mann’s 1491 Rewrote My Brain

Apocalyptic Plagues and Anthropocene Forests: How Charles C. Mann’s 1491 Rewrote My Brain

Published on July 15, 2025

Published on July 15, 2025

Published on July 15, 2025

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

Algernon Blackwood is one of the more unusual figures in The Dark Descent. An occult investigator (he was a member of the Golden Dawn and the Ghost Club during his storied life), journalist, and writer of the weird by trade, he strove in his work to instill a sense of awe, along with the idea that the world was larger than our perceptions would have us believe. His best-known work, “The Willows,” is perhaps the story that best codifies modern weird fiction, using that idea of a world beyond perception and the idea of powers beyond consciousness to show what happens when its protagonists trespass in an area controlled by natural powers beyond their understanding. While the travel, nature, and exploration tropes woven through “The Willows” remain buried in the past, it’s Blackwood’s depictions of horrors just beyond the borders of our perception that keep the story firmly in the present.

Two men set off in a canoe down the Danube, hoping to eventually navigate the length of the river. In the stretch between Austria and Hungary, they find themselves in an unnerving and treacherous area of swamps and deltas penned in by ominous willow bushes, which inspire a kind of quiet, menacing horror in the narrator. When the pair run aground on a sandy delta to make camp, the strangeness they feel blossoms into outright horror as they’re beset by strange noises, sudden windstorms, flooding rapids, and most of all, the encroaching presence of those horrid willow bushes. As the willows close in and their avenues of escape are cut off, the presence of something beyond their understanding makes itself known…and demands sacrifice.

Nature itself is inherently weird when you stop to think about it, especially for those who don’t live in its midst. While there are plenty of explanations for the weird things that happen—trees moving when there’s no wind, an odd oscillating noise humming through the air, foxes and rabbits emitting horrifying shrieks that usually set the other animals off in an endless loop of terror—for someone not used to any of that, it’s already pretty terrifying. Stories in The Dark Descent have used the natural world before to great effect, as well; “Sticks” sets the placid beauty of nature against the horror of going off to war and the disturbing ruins in the woods, “The Damned Thing” comes out of the woods and returns the same way, and most of “Young Goodman Brown” and “The New Mother” take place well outside “civilization,” in the wilderness where weird things routinely happen.

While Blackwood’s touches in “The Willows” are certainly unique—with the implied menace of the willows, the odd sand funnels, and the dread-inducing presence of whatever entities inhabit the sacrifice delta—“weird holes,” “directionless unnatural humming,” and “the feeling that trees are moving around and there’s something lurking out in the darkness” are all things that tend to happen outside. Anyone who has lived near a significant insect population can tell you that the moment the weather goes north of 80 during the day, the air is filled with hissing, humming, and oscillating sounds from noon to sunrise. Plenty of animals and bugs burrow, leaving “sand-funnels” in their wake. Blackwood touches on this at the beginning of the novella, when our protagonists witness an otter rolling around in the shallows of the delta and initially mistake it for a dead body, something that sets up the final image as the men return to their canoe at the end.

Which brings us once again to common targets of weird fiction and horror, especially in this section of The Dark Descent: the romanticization of travel and nature by those with the privilege to freely experience both. Blackwood’s novella begins with a long poetic tribute to the Danube River (a passage a colleague of mine delights in using as a kind of literary Rickroll at times) as the narrator and his companion canoe through the wilderness. Rather than marvel at the untouched beauty of nature and the protagonists’ leisurely journey through the swamps of the European riverbanks, Blackwood instead immediately strands them in a nightmare scenario where they’re forced to survive multiple nights under threat from a malevolent presence in the wilderness (a presence similar to one explored in Scott Smith’s novel The Ruins (2006), though obviously at more length and in a much more grotesque manner), effectively draining any romanticism from the travel and wilderness.

Further underscoring this, the weirdness of the island begins shortly after the travelers have an odd encounter with a local in a boat who attempts to communicate, yelling something they can’t make out due to a language barrier—the protagonists are not welcome, and the area is completely foreign to them. It could also be implied that the protagonists get the same local killed, as the “sacrifice” at the end is described as a peasant local to the region. Blackwood further swipes at exploration narratives and the idea of crashing through an unwelcome area with the “folk wisdom” dispensed by the non-native who accompanies the narrrator, the unnamed Swede, who is both a foreigner to the region and, by the time he starts talking about gods, is completely whacked out of his skull by the humming noises, wind, and encroaching willows.

Even with the explanations, it’s the quiet menace, isolation, and removal from the status quo that makes “The Willows” all the more upsetting. When one is far enough away from the comforts of daily life, the world can become every bit as alien and otherworldly as a far-off planet, a place with its own gods and rules. The certainly applies to the sacrifice delta in “The Willows,” given the obvious dangers, both natural and unnatural, that ramp up throughout the story. For all nature may be explainable, it’s still untamed— “wild” is a key component of the world “wilderness”— the besieging willow bushes, the godlike entities the narrator sees ascending into the sky, and the means the delta uses to keep its intended sacrifices penned in all point to that. The “weird” in the story is merely the intersection of an isolated patch of wilderness with its own minor gods and the narrators’ unfamiliarity with nature.

The characters’ unfamiliarity with basic nature, lack of romanticism about “The Great Outdoors” that’s found in more lighthearted works (even those where the wilderness is hostile), and direct skewering of adventure, nature, and travel narratives in which protagonists experience the bountiful idyll of their surroundings are what give “The Willows” its staying power. Its savage critique of men setting out into nature and its willingness to take what are commonplace elements of the natural world to their most menacing supernatural extremes mean “The Willows” has outlasted most of the things it was mocking, but the story’s unnerving alienness and strange, encroaching horror have ensured that its influence continues to reverberate into the modern day.

And now to turn it over to you: Why do you think “The Willows” has such an influence on the modern weird? Is Blackwood’s critique of the “great outdoors” narrative warranted? What’s the weirdest experience you’ve had when camping?

Please join us in two weeks for “The Asian Shore,” as we revisit the work of queer horror and science fiction writer Thomas M. Disch.[end-mark]

The post Without a Paddle: “The Willows” by Algernon Blackwood appeared first on Reactor.

Published on July 15, 2025

Screenshot: Paramount Pictures

Published on July 15, 2025

Published on July 15, 2025

Screenshot: Universal Pictures

Published on July 15, 2025

In June, I ended up reading a bunch of new-to-me authors more or less by accident. And, oddly enough, several with African influences. I don’t know how it happened or why, but it made my short fiction reading last month pretty exciting. It was so hard to choose my favorites, but I managed to narrow down my top ten short science fiction, fantasy, and horror stories.

For the last couple years, Osa has been stuck in the strange world of Lamprey, what she calls the Cut. She’s survived countless horrors and brutal training in her quest to return to Bronzeville. Her latest battle is convincing a creature wearing the face of her mother to trade for safe passage. But she can’t go back, not really. The girl she is now is so different from the girl who left in 1996. That won’t stop her from trying, though. The incredible twist at the end is what won this story a spot on this list. It’s the exact right ending for a story this fierce. (FIYAH Literary Magazine—Summer 2025; issue 35)

This was such a weird, creepy story. Our narrator shares a college apartment with their roommate, Helena. The place has one unexpected amenity: randomly spawning “sisters.” Helena calls them sisters as a Catholic joke, but they aren’t really people. No matter how human they look on the outside, they contain terrors within. The story is structured like a letter to the next roommate, whoever replaces our narrator after their gruesome confrontation with one of the sisters. (Fusion Fragment—June 2025; issue 25)

Told in four very short vignettes, Emma Burnett explores punishment through body horror. People must pay individually for their crimes against the planet by, well, I won’t spoil the ending but it was quite the surprise. It really got me thinking about how individuals are expected to take responsibility for the environment—recycle and compost, go vegan no matter what your culinary cultural traditions or dietary restrictions, bike ride or walk no matter your ability, no air conditioning, etc—when corporations get to do whatever they want without restriction, and who pays the price. (Radon Journal—issue 10)

In this fantasy world similar to our own, a South Indian culinary magician earns a scholarship to a prestigious magiculinary school, The Diner University. Although known for her flavorful idli sambar, Deepika’s dishes don’t go over so well with the Westernized palates of her professors. She faces a choice: flatten her dishes or stick to tradition. When the keys to success are bound up in getting Westerners to like you, the decision isn’t necessarily an easy one to make. Maroon Stranger (tremendous name!) could have made this story dark or sad, but she opted for a hopeful tone, one that celebrates community. (Luna Station Quarterly—June 2025; issue 62)

Mai Alfred is the CFO of a company about to build a bunch of swanky hotels in Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe. She doesn’t care that the construction will force the Indigenous Kupona people off their land—even though her greed has cost her not only her marriage but the affection of her only child. If that won’t put her off the project, the rumors of the Kupona practicing witchcraft won’t either. Too bad those rumors turn out to be real. A great story that touches on the ways colonialism is passed onto and sustained by the colonized. It also has a lot to say about the limitations of feminism when it’s used to uphold Western traditions at the expense of other women.(Strange Horizons—June 30, 2025)

Look, I am terrified of spiders. I don’t like them. At all. I don’t even like reading about them. I nearly DNF’d R.L. Meza’s story once I realized it was about humans mutated into arachnids, but I’m glad I powered through because this story is compelling in an unsettling kind of way. The narrator is trapped in a tank, one of many in an underground lab. A scientist known only by her nametag, “A. Friend,” kidnapped her ages ago and has been torturing them all ever since. When an opportunity for escape presents itself, the narrator leaps. (Clarkesworld—June 2025; issue 225)

Oladeo and Nnadi’s unconventional courtship leads to unconventional pregnancies. Three times in a row, Oladeo gave birth to twins, seen as bad luck in her village. Twice she watched as the midwives took the newborns away to kill them. Once she fought back. This story is a bit fantasy and a bit science fiction. Somto Ihezue pulls on real folklore from the Igbo of Nigeria that holds that twins are bad omens. All Oladeo and Nnadi can see are two helpless infants they love more than they can say. (Diabolical Plots—June 16, 2025; #124B)

I love reading stories set during historical events I know nothing about. I get to learn something new while also enjoying a good tale. This fascinating story was set in Klang, Malaysia, where author Joshua Lim is from, just before the Japanese invasion in World War II. Seven-year-old Hong Ang and his family are Chinese and at the greatest risk of being imprisoned or worse. They seek refuge on Pulau Ketam, an island just off the coast of Port Klang, and beseech the protection of spirits they call the swampmasters. (Khōréō Magazine—volume 5, issue 2)

Speaking of Nigerian folklore, Ogochukwu Bibiana Ossai delves into Yoruba culture with the abiku, the spirit of a child who dies before their thirteenth birthday. In Yoruba folk tradition, the abiku can return to the same mother over and over again, with each rebirth ending in the child’s death. Here, the spirits of twelve dead children, all iterations of each other, connect in another world made of “glass rocks, cracked honey earth, coarse red sand, rugged terrains, a cotton sky that looked like the seas of lava, and trees with deep dark green boughs and twigs.” There they consider what they lost and what their mother lost. (The Dark—June 2025; issue 121)

This flash sci-fi story made my heart ache. Years ago, someone planted a decorative crab apple tree in a garden on the Miranda Spaceport. The tree, our narrator, has watched humans come and go over the years, but feels particular affection for two young men, Jun and Elliot. As the spaceport is being decommissioned and humans sent to the far reaches of the galaxy, the men face a potentially permanent separation. As each tries to convince the other to go with them, the crab apple tree tries to help them one last time. It’s a beautiful, kind story, and the perfect one to close out this list. (Apex Magazine—June 2025; issue 150)

[end-mark]

The post Must Read Short Speculative Fiction: June 2025 appeared first on Reactor.

Published on July 15, 2025

Photo Credit: Pari Dukovic/Paramount+

Whenever I rewatch Seinfeld, I’m struck by how many classic moments in the show involve the core characters recapping events that have already happened. Elaine talking about running into John F. Kennedy Jr. at the gym, Kramer recounting seeing the pig man, George’s “the sea was angry that day, my friends” monologue, or “He took it out.”

It’s a very common sitcom approach in general, whether it’s brunch in Sex and the City or Tim and Wilson talking over the fence in Home Improvement.

But recapping something that’s already happened very rarely works in a novel. Put a great deal of thought into what you choose to dramatize and what you leave off the page.

I’ve written previously about the dangers of screenplay-izing or teleplay-izing your novel. Some writers inevitably default to movies and TV shows when they’re imagining their novels. The problem is that this often results in plodding, dialogue-centric novels where characters are just standing around endlessly chitchatting.

When we watch TV or movies there’s far, far more that we’re absorbing than the dialogue. There’s a setting, facial expressions, gestures, inflection, sound effects, physical presence, movement… If all you’re providing is dialogue and you’re neglecting physical description and gestures, you’re not even replicating the information we’re receiving when we watch a TV show.

You’re also missing the interiority that makes novels such a unique and powerful medium. We don’t have the chance to see and feel a moment in a TV show from inside a character’s head like we can in a novel.

There are a whole lot of reasons a recap works in a sitcom. Actors can be funny, and it’s enjoyable to see characters’ reactions to what’s being said as a proxy for our reactions (something Japanese TV understands extremely well). Not to mention practical considerations like not having the budget to show George Costanza saving a whale.

But most importantly: recaps leave more to the viewer’s imagination. Imagining George atop a whale is a whole lot funnier than actually seeing some bad CGI approximation.

In novels, everything is the reader’s imagination. Recapping doesn’t create a gap for more imagination, it just means we’re another step removed from experiencing a dramatic moment ourselves.

In short: build your novel so that your reader experiences the most dramatic moments for themselves. There’s a great deal of power in experiencing events along with the protagonist(s) and seeing and feeling their reactions in the moment.

If all we’re getting is recaps of dramatic scenes after the fact, we’re distanced from what happened. It gets confusing about why we’re seeing what we’re seeing and what the narrative voice is choosing to show us. It can feel like the author is playing “keep away” with the good stuff.

Put a great deal of thought into what you keep on and off the page. Err on the side of including the dramatic moments and brushing past mere movement from Point A to Point B.

There are, of course, exceptions to this. There are novels like Absalom, Absalom! that involve recapping and some unspoken moments that happen off the page, and we mainly see them refracted in the aftermath.

But that was a very conscious choice for very specific reasons. The unspeakableness of some of the events was the point. It was not because William Faulkner just found it easier to write scenes centered around dialogue than he did describing action.

Dramatize your most important events, and better yet, build your novel around them.

On the flip side, if you put tedium on the page, the reader is going to be tempted to skim forward to get to the good bits, or put down your book entirely. As Elmore Leonard famously said, “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.”

Remember: your goal when writing a novel is not to replicate real life, it’s to tell a good story.

Readers are capable of filling in gaps in everyday chores. They’ll assume characters are eating, breathing, and going to the bathroom without needing those realities spelled out on the page. They’ll assume all necessary pleasantries have been exchanged when characters meet each other.

They can infer that when a character moves from Point A to Point B they did, well, whatever they needed to do to get there. While it’s good to provide the broad strokes of how characters move around so it doesn’t feel like they pop out of nowhere, we don’t need every single uneventful step filled in.

In real life, people get aimless, bored, and stuck, but in a novel, it’s usually better to brush past the aimlessness to get to the parts that push the story forward. Remember: if your protagonist is bored, chances are your reader will be too.

In novels, you can speed up and slow down time at will. You can brush over a thousand years, or dwell on a split second for dozens of pages. Readers will largely roll with it, as long as you’re pushing the story forward.

One crucial way of doing that is to keep the protagonist active. Err on the side of constructing scenes after a character who’s doing or trying to figure out something, and brush past the parts where they’re stalled out or waiting for something to happen.

Be judicious and thoughtful about what you dramatize. Utilize the unique properties of novels as an art form rather than trying to imitate Sex and the City brunches.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED: July 11, 2022

Need help with your book? I’m available for manuscript edits, query critiques, and coaching!

For my best advice, check out my online classes, my guide to writing a novel and my guide to publishing a book.

And if you like this post: subscribe to my newsletter!

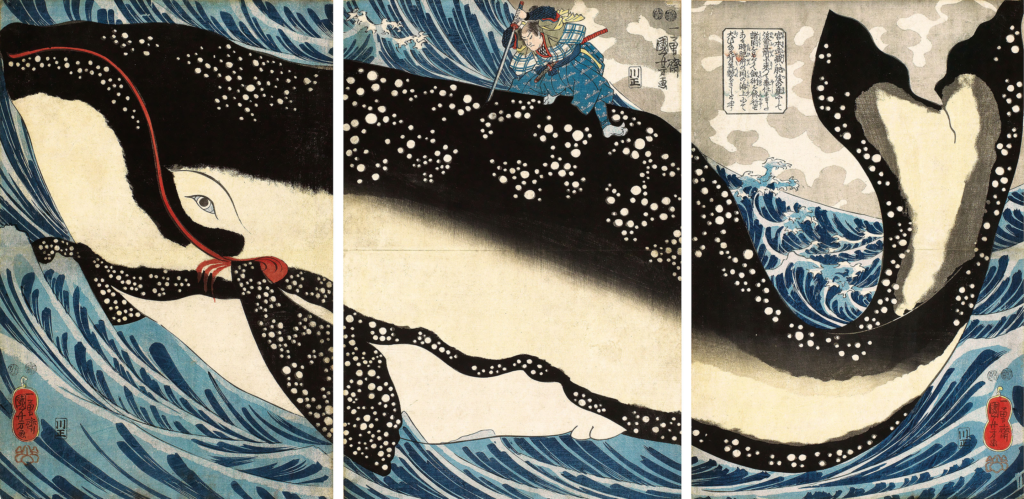

Art: Miyamoto Musashi Attacking Giant Whale by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Published on July 14, 2025

Screenshot: Marvel Studios

Published on July 14, 2025

Photo by Niko Nieminen [via Unsplash]

Photo by Niko Nieminen [via Unsplash]

In my quest to work through all the tabletop roleplaying games that I own but have never run, I am currently gamemastering Fabula Ultima. Part of the attraction is that FU encourages a collaborative approach between players and gamemaster, an approach with which I am not especially comfortable. Personal character growth (for me at least) is inevitable.

In accordance with the collaborative narrativist spirit of the game, I have dialed back my control freak tendencies, which is why, while my master player character chart lists names, core stats, figured stats, defensive stats, classes and which class abilities each PC possesses, it does not detail what each ability does, nor does it list spells1.

All of which brings me to my question: Why are charts so cool2?

On a personal level, the charts I create for tabletop roleplaying games3 are a means of circumventing unreliable memory. All the character names are right there at my fingertips… provided I remember to open the relevant file. The charts I create for the works I review serve a similar purpose as I juggle a number of often incompatible review goals. Much the same is true for charts documenting the books I receive, especially since I don’t seem to have object permanence for ebooks.

More interestingly, a well-designed chart will highlight patterns that might otherwise be overlooked. This ensures that I do not, for example, build an entire scenario around player character abilities that none of the PCs actually have4, or spend an entire year without reviewing any books by women, or, on a more positive note, determine that no single publisher had a lock on Best Novel Nebula Awards, reveal that SFF authors prefer oligarchies to other forms of government, and that publishers currently seem oddly shy about unambiguously labeling books as part of series. Or, in what was for me an astonishing finding, that charts tracking absences are extremely confusing for most people. I didn’t know that! But now I do.

Most importantly, a well-designed, well-presented chart is a thing of beauty. What could possibly match the endorphin rush triggered by glorious data presented in an eye-catching, easily-comprehended format? Charts to order chaos, they illuminate an often-murky world, they make us as gods5!

At least, that’s why I love charts. No doubt there are dozens of equally compelling reasons to adore charts6. If I’ve overlooked your favorites, feel free to mention them below.[end-mark]

︎

︎ ︎

︎ ︎

︎ ︎

︎ ︎

︎ ︎

︎The post Why Do I Love Charts? Let Me Count the Ways. appeared first on Reactor.

Published on July 14, 2025

Credit: Warner Bros. Television

Published on July 14, 2025

Photo by Aaron Burden [via Unsplash]

Photo by Aaron Burden [via Unsplash]

POV is one of those writing issues that get a little bit thorny—because there are people out there who will tell you there are Strict Rules about how many POVs you can have, and how much you can shift between them, and so on.

A lot of people seem to hate omniscient narrators—despite the fact that many of the world’s most beloved books are written in omniscient third person. But also, some very influential writers advocate a strict economy of viewpoints, in which a book must establish its POV characters early on and not introduce any more POVs later on, no matter how convenient it might be to see events from a particular character’s perspective.

Because I don’t believe in rules—literally, there are no rules when it comes to writing—I feel like you should use as many POVs as you want to, as long as they’re helping you tell the story in the most entertaining, immersive way possible. Have a single first-person narrator, or a few. Have a single third-person POV, or a ton. Go omniscient, whatever. Go nuts.

The question of who gets to have a POV in a story is artistic—but also kind of political, because it goes to the heart of whose perspective counts.

When I started out writing fiction as a career, I mostly wrote in the first person, because I love a mouthy, obnoxious first-person narrator. But I kind of hit a wall, and I read some writing advice that said it was easier to sell short stories written in the third person. Plus writing in the third person felt like a fun challenge, so I switched. And sure enough, I found that writing in third person forced me to describe things differently, and to think about the position of the narrator in relation to the events in a way that I hadn’t with first person. (The first draft of Lessons in Magic and Disaster was written in first person, but I changed it to third person in revision for a similar reason.)

My first novel, Choir Boy, has a single third person POV, that of the main character, Berry. But the narrator is free to make all sorts of silly observations about the town where Berry lives—like, I think there’s a long elegiac section about the slow decline of the noodle-stretching factory across the street from Berry’s apartment at one point. Still, I kept my narrator from going too omniscient, because I’d internalized a strong prohibition (especially in science-fiction circles) on “head-hopping,” or allowing the reader to glimpse more than one character’s thoughts at any given moment. I had learned to think of an omniscient narrator as the third rail of fiction: touch it at your peril.

Imagine my surprise when the biggest successes of my career came from a novelette called “Six Months, Three Days” and my novel All the Birds in the Sky, both of which feature gently omniscient narration. There’s one moment in All the Birds in the Sky that I was convinced would make people rage-quit the book. It’s the bit where Laurence and Patricia are sitting under the escalator speculating about people based on their shoes—and then the narrator reveals that they’ve guessed correctly about the last guy who went past, who is indeed an assassin named Theodolphus Rose. I almost cut this bit several times, convinced people would tell me it was the reason they abandoned the book. Instead, people kept telling me it was their favorite moment in the entire book.

Lately, I’ve read more and more books that casually throw in extra POVs here and there—some side character who’s only stood in the background of scenes will suddenly have a POV chapter in the final stretch of the book. I feel like young-adult fiction started playing fast and loose with POV in the 2010s, and this has now seeped into adult fiction. I’ve also seen more ambitious experiments, like The Ten Percent Thief by Lavanya Lakshminarayan, where each chapter is told from a brand new POV.

Some of my favorite memories of reading involve surprising POV shifts—like, I remember being a kid and reading Terrance Dicks’ surprisingly good novelization, Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion. Dicks would dip into the head of a random side character for a few paragraphs, someone who might not have even gotten any dialogue on screen, and it was dazzling. Everyone has their own opinion, even the guy standing in the corner while the Doctor grandstands!

There’s something kind of magical about realizing that everyone in a story is a person, and nobody is an NPC.

Still, I have often found myself feeling cautious about adding more POVs to a story—because I do have the sense that a POV should be immersive. In other words, you should fully inhabit the mind of a character if you’re going to see through their eyes. It’s a bit of an imaginative lift each time, which requires you to think about who this person is, where they come from, how much information they have, and what’s going on. I do think that even if a POV only appears a couple of times in a long book, you need to make sure there is a unique attitude and set of concerns animating this person, so it stands out from the other POVs at least somewhat.

I get more annoyed when a book has multiple first-person narrators whose voices are too identical—but even with third-person POVs, ideally you want them to be thinking differently. It’s sort of the same problem as when all your characters talk the exact same way.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about POVs, because I’ve found out the hard way that it’s super challenging to make readers fully identify with someone whose thoughts we never experience. I’m not saying it’s not doable, it’s just tough—especially with characters who make unsympathetic choices or behave even a little selfishly.

When I wrote The City in the Middle of the Night, I decided that only Sophie and Mouth would have POVs in the book. (In fact, originally it was going to be just Sophie, and after I had written a couple of drafts I realized the book needed more of an edge, so I promoted a random smuggler to a second POV.) At the time, making Sophie first-person present tense and Mouth third-person past tense felt a bit daring, even though young adult fiction had been doing this sort of thing a lot.

Anyway, at a certain point I ran into a question: should I give Bianca some POV chapters as well? For those who haven’t read the book, Bianca is someone who starts off idealistic and radical (but unaware of her own privilege in various ways), and she ends up becoming a bit of a monster. I have a certain amount of sympathy for Bianca, even though her actions are unforgivable. (I also have a sneaking suspicion that if Bianca were a man, she would have had a lot of people defending her and demanding a redemption arc.) In any case, I toyed with giving her a POV, to make her actions more legible to the reader. But I didn’t want to give her equal space to Sophie and Mouth, and I wasn’t sure if it would work to just dip into her POV a couple of times. More importantly, I wanted to preserve the surprise of Bianca’s heel turn, and I didn’t think I could do that while letting people in on her thought process.

I’ll never know how things in the book would have turned out if I’d given Bianca some POV chapters, but on balance I’m glad I didn’t. It kept the focus on what I wanted the book to be about: Sophie and Mouth both bought into other people’s ideals of justice and community, and they both learn the hard way that they need to make their own.

But more recently, I have been finding that when in doubt, it’s usually a good idea to give someone a POV. In my upcoming novel Lessons in Magic and Disaster, I originally included only a couple of brief sections from the POV of Jamie’s mother Serena. And I found some of my beta readers had a hard time feeling invested in Serena or understanding why she does the things she does in the story. The book fails miserably unless you care what’s happens to Jamie’s mom. And I have so much love and empathy for Serena, someone who consistently tries to do the right thing and struggles to shoulder the weight of grief and trauma.

So I gave Serena way more space in the book, including a huge chunk of flashbacks to her early years as an activist and her marriage to Jamie’s other mother, Mae. As soon as I did this, it was obviously the right choice: it deepened all of the other themes and relationships in the book to have this level of understanding of Serena’s joys and struggles.

So lately, I’ve been thinking about the politics of POV.

The issue of whose perspective is included in a story feels inherently political. A character who’s only seen from the outside inherently becomes a bit of a cipher—or an NPC, as I said above. I wrote before about the idea that we should stop talking about characters having agency in a story and instead talk about whether a character gets to be an authority on their own life. The characters who matter in a story tend to be the ones whose opinions shape how we feel about the overall events.

So as I start crafting my next couple of novels, I’m increasingly thinking about how to be a bigger POV slut—because I think it’s a matter of simple fairness to allow as many voices as possible to exist within the story.

I do think a POV character needs to pull their own weight narratively—not just in terms of witnessing events that nobody else in the story could have witnessed, but also by adding a different sensibility. Or set of concerns. Or something that might change how we think about the story a bit.

Especially when someone is a character that readers might be predisposed to judge harshly because of internalized prejudices, I think it’s important to try to represent that person’s viewpoint in the story. But also, people whose actions shape the narrative, in ways that feel startling or confusing, can really benefit from getting to tell their side of the story. Lately I’m noodling on the idea that it’s not so much a question of “How can I structure the story in such a way as to keep the narrative moving” as “Who is being silenced in this story, and do they deserve a voice?”

I guess I’m craving more anarchy in my stories, because I have read some stories lately that were gloriously promiscuous in their use of viewpoints, and I was surprised by how much it enhanced the experience. And because I feel like the dominant experience of 2025 is being trapped in our own perceptions of reality, with less and less ability to know how other people are thinking and feeling about the same events. One of the great joys of fiction is that it lets you understand that any one event can be understood from many different angles. (See: Rashomon.)

A few caveats apply: I still love an omniscient narrator and I’m probably going to try to keep making that happen. Also, here’s where I admit that my next novel, the one that I’m hoping comes out in 2026, has only one POV for reasons that I hope will become clear. Finally, I do think that if a POV fails to stand out or feel unique, it can be worse than not going into that person’s mind at all.

All in all, though, I have been getting the feeling lately that the era of POV puritanism—the idea that you gotta pick a small number of major POVs and stick to them—is over, and the era of “anything goes” has begun. And I couldn’t be happier, not just from a writing standpoint but also from a standpoint of wanting to experience as many ways as possible of looking at a story within that story.[end-mark]

This article was originally published at Happy Dancing, Charlie Jane Anders’ newsletter, available on Buttondown.

The post Who Gets a POV In Your Story? It’s a Political Decision appeared first on Reactor.

Published on July 14, 2025

Photo by Ranae Smith [via Unsplash]

Photo by Ranae Smith [via Unsplash]

On the opposite end of the cute spectrum from the orca is what we mostly mean when we say “dolphin”: the bottlenose dolphin made popular by films and television shows, notably Flipper, and some of its relatives including the spinner and the spotted dolphin. Orcas are actually the largest of the dolphins, and both are, more broadly, toothed whales, related to the beluga and the sperm whale (versus baleen or krill-sifter whales like the humpback). Toothed whales are predators, and as a class, they’re highly intelligent. We’ve certainly seen that when it comes to orcas.

Dolphins with their playful personalities, relatively unthreatening size, and their naturally adorable, smiling faces are the most appealing and accessible of the cetaceans. They seem to enjoy human contact, or at least not to be overtly stressed or terrified by it. “Swimming With Dolphins” experiences are a staple of the vacation industry.

Human-dolphin contacts go back a long way. There’s an ancient Greek story of a man called Arion, a poet and singer who had been robbed and thrown overboard by the crew of a ship. A dolphin rescued him and carried him on its back to the shore. May be a myth. May not be. It’s not impossible, from what we know of dolphins.

These are highly social animals. They live in pods or family groupings, and they have a language, though it’s not exactly like the human version. It appears that they have names, and call each other by them. They hunt together, and they use strategy and tactics. They play—constantly, enthusiastically, creatively.

And they use tools. Take for example the dolphins of Shark Bay in Australia. A particularly sprightly series of articles describes two different groups, the spongers and the shellers (as well as the beachers, who herd fish to shore and beach themselves to feed).

The spongers select a sponge from the sea bed and fit it to their noses, and use it as a sort of glove to protect their skin while they forage for sea perch. They’ll carry a sponge around and reuse it. It’s not a natural or instinctive behavior; it’s passed down from mother to daughter and sometimes son. Spongers tend to associate with each other, share tips and finer points, and refine their art as they mature.

Shellers are a different cultural group, a bit more equally divided between the sexes. They lift giant sea snail shells from the bottom, scoop up fish, carry the shells to the surface, wiggle and flip them over, and dump the fish into their mouths. The level of sophistication it takes to do this, and the number of steps and the degree of finesse, is pretty impressive.

But not all that surprising. Dolphins have big brains for their size, comparable to humans. Also like humans, they have a highly developed neocortex (associated with problem-solving and self-awareness among other things) and Von Economo neurons, which are linked with emotions and social cognition. There’s a lot going on there; how much, we’ve barely begun to understand.

We want to. We try. Someday maybe we’ll crack the code of dolphin language. We’ll learn more about how they perceive the world: how their sonar works, and what it feels like.

We know it can act like ultrasound, allowing them to see into and through a solid body. They’re fascinated by pregnant human swimmers. Imagine being able to look at another person and see what’s going on under the skin, and know what’s happening inside. We have to invent machines for this. Dolphins come with it already installed.[end-mark]

The post Everyone’s Favorite Cetacean: The Dolphin appeared first on Reactor.

Published on July 14, 2025

This week! Books!

Lots of links saved up over the past few weeks, let’s get to them!

Anthropic Scores a Landmark AI Copyright Win—but Will Face Trial Over Piracy Claims – Kate Knibbs, Wired – In a huge ruling on A.I. and copyright, a federal judge agreed that using books to train A.I. is fair use, but Anthropic will stand trial over pirating books. Basically, the judge said Anthropic could have used books to train for A.I. if they’d actually paid for them. A mixed result for authors.

A Different California Judge Believes LLMs Are Likely Infringing Much of the Time, But Authors Made the Wrong Argument So Meta Case Is Dismissed – Michael Cader, Publishers Lunch – In a separate trial, a judge dismissed a lawsuit against Meta over A.I., but suggested the authors were making the wrong arguments and charted a course for a successful lawsuit that argues LLMs are infringing authors’ rights by appropriating work in a way that creates market harm for authors.

Supreme Court Rules That Parents Can Opt Out of Classes Using LGBTQ+ Books – Katy Hershberger, Publishers Lunch – And in yet another ruling, the Supreme Court ruled that parents can remove their children from lessons where “LGBTQ+-inclusive” books are used.

In Wake of Court Losses, Rhode Island Codifies ‘Right to Read’ – Sam Spratford, Publishers Weekly – And in response to the censorious cultural and legal atmosphere, Rhode Island became the latest state to codify protections for librarians and affirming authors’ right to sue for censorship.

I look forward to a time when legal rulings aren’t among the most important news items in the publishing world.

Authors petition publishers to curtail their use of AI – Chloe Veltman, NPR – More than 70 authors signed an open letter urging publishers to promise they will never release A.I.-generated books.

How local bookstores are helping immigrants amid ICE fears – Victoria Ivie, San Gabriel Valley Tribune – Amid horrifying masked raids and military escalations in the Los Angeles areas, local bookstores are serving as crucial community hubs with mutual aid groups to provide support for the immigrant community. As if we needed another reason to love independent bookstores!

Berkley, Penguin Young Readers Team Up on New Imprint – Sam Spratford, Publishers Weekly – I often discourage authors from pitching the “crossover” appeal of their novels, because for a long time, there really was no such thing. Sometimes books break out of their core genre and get retroactively labeled a crossover hit, but agents and publishers specialize and adult and YA novels sit on completely different shelves in bookstores. Well. Two imprints at Penguin Random House are now teaming up on an adult-YA crossover imprint, so the times may be changing.

Accusations of plagiarism, AI use and author bullying: ‘BookTok’ rocked by recent scandals – Kalhan Rosenblatt, NBC News – You will be shocked, SHOCKED to learn that there is author drama on TikTok.

Marginalia mania: how ‘annotating’ books went from big no-no to BookTok’s next trend – Caitlin Welsh, The Guardian – The kids have discovered marginalia.

The Plight Of The White Male Novelist – Sarah Brouillette, Defector / When Novels Mattered – David Brooks, New York Times / The Forever Dying and the Always Dead; or, Literary Fiction and the Novel – Lincoln Michel, Counter Craft – Grouping these together because there has been a ton of #Discourse lately around literary novels and, in particular, the state of the male novelist. (Will no one think of the men, lol!) Lincoln Michel makes the most persuasive case that much of this discourse revolves around false glory days and the rise of mass consumerism across all media. He also pre-debunked claims Brooks made today in his column.

What Reading 5,000 Pages About a Single Family Taught Me About America – Carlos Lozada, New York Times – Speaking of which, in contrast to the gauzy nostalgia about past literary golden eras, one of the actual biggest bestsellers of the ’70s and ’80s was a pulpy multi-generational historical melodrama that followed a single family through American history, written by then-household name John Jakes. Carlos Lozada has a thoughtful essay on what the series meant then and now.

The Critic and Her Publics – Merve Emre, LitHub – Merve’s one of the smartest critics in town, and her fantastic podcast season on what it means to be an editor is now fully available in transcript form.

In This Parisian Atelier, Bookbinding Is a Family Art – James Hill, New York Times – Very cool images and video of an artisanal bookbinder in Paris keeping the dream of beautiful print books alive.

Sprayed Edges Are Everywhere and I Hate Them – Selah Jordan, Paste – Also in bookbinding news, Selah Jordan has some thoughts on the rise of sprayed edges, which have become ubiquitous in romantasy.

Inside the Salt Path controversy: ‘Scandal has stalked memoir since the genre was invented’ – Lucy Knight, The Guardian – The latest memoir scandal is brought to you by Salt Path. These have literally been going on since the concept of a memoir was invented.

Moral Rights: What Writers Need to Know – Victoria Strauss, SFWA – The indispensable Victoria Strauss discusses a lesser-known dimension of author rights, and what to consider if you’re asked to give up moral rights.

The truth behind the endless “kids can’t read” discourse – Constance Grady, Vox – Are the kids really reading less or are we all just getting old? Constance Grady delves into what we do and don’t know about whether the kids are reading.

Here are the top five NY Times bestsellers in a few key categories. (All links are affiliate links):

Adult print and e-book fiction:

Adult print and e-book nonfiction:

Young adult hardcover:

Middle grade hardcover:

In case you missed them, here are this week’s posts:

And keep up with the discussion in all the places!

And finally:

Seven Days At The Bin Store – Jen Kinney, Defector – A fascinating look at the rise of bin stores, and what they mean for our era of late stage capitalism.

Have a great weekend!

Need help with your book? I’m available for manuscript edits, query critiques, and coaching!

For my best advice, check out my online classes, my guide to writing a novel and my guide to publishing a book.

And if you like this post: subscribe to my newsletter!

Photo: Sea Ranch, CA. Photo by me.

Published on July 11, 2025

Lucas photo courtesy of Skywalker Properties Ltd.; Museum construction photo by Sand Hill Media/Eric Furie

Lucas photo courtesy of Skywalker Properties Ltd.; Museum construction photo by Sand Hill Media/Eric Furie

On Sunday, July 27, 2025, George Lucas, the creator of Star Wars, will make his way to the Hall H stage at San Diego Comic-Con for the first time. The reason he’s there, however, isn’t for a galaxy far, far away: It’s to discuss the power of illustrated storytelling, and also give the audience a sneak peek of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, which is nearing the end of construction in downtown Los Angeles.

The panel, descriptively titled “Sneak Peek of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art,” will be moderated by renowned singer and actor Queen Latifah, and Lucas will be joined onstage by Guillermo del Toro (Hellboy, Crimson Peak, and many other great films) and artist Doug Chiang, who for decades has been shaping the look and feel of Star Wars universe.

“We are beyond thrilled to welcome George Lucas to Comic-Con for the very first time,” David Glanzer, Comic-Con’s chief communications and strategy officer said in a statement. “Nearly five decades ago, Star Wars made one of its earliest public appearances at our convention, along with a booth featuring Howard Chaykin’s now legendary Star Wars poster as a promotional item. Now, to have Mr. Lucas return—this time to debut the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art—is a true full-circle moment. His lifelong dedication to visual storytelling and world-building resonates deeply with us and our community, and the museum’s mission to celebrate narrative art in all its forms perfectly reflects what Comic-Con has championed from the very beginning.”

The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art was co-founded by Lucas and Mellody Hobson, and is set to open in 2026. It will feature art from Norman Rockwell, Kadir Nelson, Jessie Willcox Smith, N. C. Wyeth, Beatrix Potter, Judy Baca, Frida Kahlo, and Maxfield Parrish; as well as comic art legends such as Winsor McCay, Jack Kirby, Frank Frazetta, Alison Bechdel, Chris Ware, and R. Crumb; and photographers Gordon Parks, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Dorothea Lange. It will also house the Lucas Archive, which contains props, models, concept art, and costumes from Lucas’ filmmaking career. [end-mark]

The post George Lucas Heads to San Diego Comic-Con for the First Time — to Promote His Museum appeared first on Reactor.

Published on July 11, 2025

Published on July 11, 2025

Author photo: Quirk Books

Published on July 11, 2025

Screenshot: Warner Bros.

Published on July 11, 2025

Image: Apple TV+